Alcohol use disorder and depression in resource-limited settings: health service utilisation, barriers to care, and treatment gap

NCYSUR Postdoctoral Fellow Dr Tesfa Mekonen Yimer reports on his PhD research on mental health systems in low resource settings, particularly focusing on depression and alcohol use disorder.

Why it matters

Mental and substance use disorders are among the leading causes of disease burden worldwide. In 2001, it was estimated that 450 million people had neuropsychiatric disorders [1], a figure that more than doubled by 2019 [2, 3]. Over 80% of those affected by mental and substance use disorders live in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) [2], where resources and infrastructure are often insufficient [4].

Our focus on alcohol use disorder (AUD) and depression is due to their high prevalence, burden, and frequent comorbidity. AUD and depression account for 36.2% of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) attributable to mental and substance use disorders globally [2]. Additionally, depression is projected to become the second leading cause of disease burden by 2030 [5], while AUD is the most common of all substance use disorders [6]. The high comorbidity rate between depression and AUD, where depression occurs in approximately 20% of individuals with AUD [7, 8], further emphasizes the need for research. If left untreated, the burden of these conditions will likely continue to grow. Given their significant contribution to the global disease burden, examining treatment rates and health service utilisation for individuals with AUD and depression is crucial to identify barriers and inform policymakers.

Our research approach

This research employed multiple approaches including systematically reviewing and analysing existing studies, in-depth interview of healthcare providers, and community based cross-sectional surveys. To provide context for AUD and depression health services in low-resource settings, we included data from both LMICs and high-income countries, with a specific case study focused on Ethiopia in our analyses.

Key findings

Substantial treatment gap

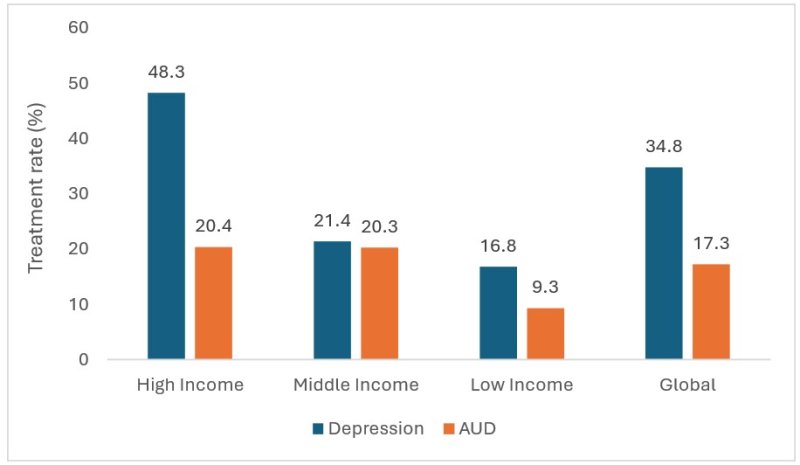

The global treatment rates were 17.3% for AUD and 34.8% for depression. The treatment rate for AUD in low and lower-middle-income countries was 9.3% (read full text here). The treatment rate for depression in low-income countries was 16.8% (read full text here).

Fig 1: Treatment rates of AUD and Depression from any source of treatment

Generally, only one in six people with AUD and one-third of people with depression received treatment. In other words, 83% of people with AUD and 65% of people with depression are left untreated [9, 10]. There are many reasons why many people do not get treatment for AUD and depression, including the belief that the problem will resolve itself. This raises the question of what proportion of people with these conditions will experience remission without treatment. This treatment gap is particularly pronounced in LMICs, where the treatment rates are considerably lower. In these resource-limited settings, only one in ten people with AUD and one in six people with depression received treatment. For instance, in Northwest Ethiopia, 19.6% of people with depressive symptoms and 1.3% of people with AUD symptoms sought treatment from healthcare or non-healthcare settings, which translates to an 80.4% treatment gap for depression and a 98.7% treatment gap for AUD symptoms [11].

Barriers to seeking treatment

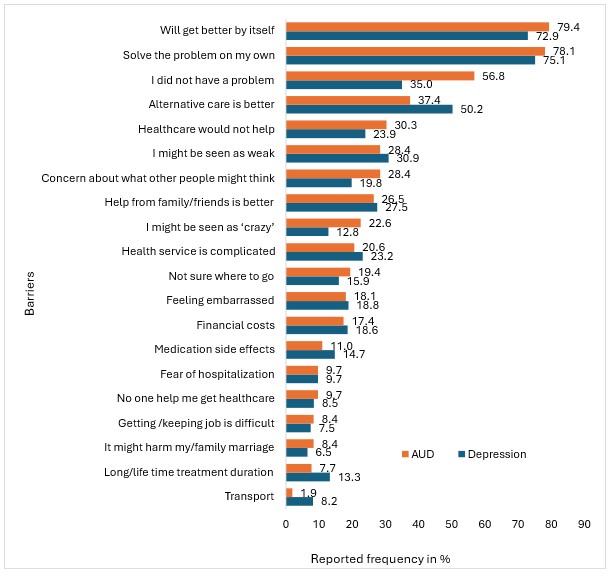

People with AUD and depression may not perceive the need for treatment or may not consider their illness to be treatable. In Northwest Ethiopia, the most frequently reported reasons for not seeking or delaying treatment for symptoms of AUD and depression were associated with a low perceived need for treatment (read full text here).

Fig 2: Barriers to seek treatment from healthcare settings for symptoms of AUD and depression in Northwest Ethiopia

The perception that symptoms of AUD and depression could remit spontaneously without treatment may deter people from seeking treatment and undermine the perceived urgency of health systems to resource healthcare adequately. For example, the top two reasons for not seeking or delaying treatment by people with symptoms of AUD and depression were the assumptions that the problem will resolve itself and attempting to handle the problem on their own (Fig 2). This low perceived need for treatment is an important indicator of the low level of health literacy in the community.

Untreated remission is rare

To estimate the proportion of people who might achieve remission from AUD and depression without treatment, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis. There was an existing systematic review published in 2019 that addressed the untreated remission of AUD [12]. According to this review, the rate of remission in people with untreated AUD ranges from 2.7% to 64%, with a median remission rate of 15%. We conducted our own systematic review and meta-analysis for untreated remission of depression, and we found that only 12.5% of people with untreated depression remitted within 12 weeks [13]. While untreated remission may occur in some cases of depression and AUD, it is important to keep in mind that the vast majority (over 85%) of people will continue to experience symptoms (read full text here).

Implications

The scarcity of health services in LMICs, including Ethiopia, is well documented. However, individuals with AUD and depression often do not utilise even the limited services available. Many untreated individuals do not want to seek treatment for these conditions, but this should not result in them being overlooked in mental health service planning. Instead, the underlying reasons for the low perceived need for treatment must be addressed. Common reasons for not seeking treatment include the belief that AUD and depression are either untreatable or can be resolved without intervention, reflecting low levels of health literacy. Thus, improving health literacy is just as important as enhancing the availability and accessibility of health services in LMICs like Ethiopia.

Cultural and religious practices also play a crucial role in influencing health service provision and utilisation. In Ethiopia, AUD and depression are often conceptualised through traditional and religious lenses, which shape help-seeking behaviours and treatment preferences. Many individuals turn to healthcare services as a last resort, only after exploring traditional and religious options [14, 15]. Therefore, integrating these existing pathways of care, including religious and traditional sources, into the broader health system could help increase coverage for AUD and depression treatment.

References

- WHO. (2001). The World Health Report 2001: Mental Health: New Understanding, New Hope. Geneva: World Health Organization. Available from https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/42390.

- Global Burden of Disease Collaborative Network. (2020). Global Burden of Disease Study 2019 (GBD 2019) Results. Seattle, Washington: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). Available from https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results/.

- WHO. (2017). Depression and Other Common Mental Disorders: Global Health Estimates. Geneva: World Health Organization. Available from https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/depression-global-health-estimates.

- WHO. (2021). Mental Health Atlas 2020. Geneva: World Health Organization. Available from https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/345946.

- Mathers, C. D., and Loncar, D. (2006). Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030 (Projections of Global Mortality). PLoS Medicine, 3(11), e442. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0030442.

- Degenhardt, L., Charlson, F., Ferrari, A., Santomauro, D., Erskine, H., Mantilla-Herrara, A., Whiteford, H., Leung, J., Naghavi, M., Griswold, M., Rehm, J., Hall, W., Sartorius, B., Scott, J., Vollset, S. E., Knudsen, A. K., Haro, J. M., Patton, G., Kopec, J., Carvalho Malta, D., Topor-Madry, R., McGrath, J., Haagsma, J., Allebeck, P., Phillips, M., Salomon, J., Hay, S., Foreman, K., Lim, S., Mokdad, A., Smith, M., Gakidou, E., Murray, C., and Vos, T. (2018). The global burden of disease attributable to alcohol and drug use in 195 countries and territories, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Psychiatry, 5(12), 987-1012. DOI: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30337-7.

- Brière, F. N., Rohde, P., Seeley, J. R., Klein, D., and Lewinsohn, P. M. (2014). Comorbidity between major depression and alcohol use disorder from adolescence to adulthood. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 55(3), 526-533. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2013.10.007.

- Caetano, R., Vaeth, P. A. C., and Canino, G. (2019). Comorbidity of lifetime alcohol use disorder and major depressive disorder in San Juan, Puerto Rico. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 80(5), 546-551. DOI: https://doi.org/10.15288/jsad.2019.80.546.

- Yimer, T. M., Chan, G. C. K., Connor, J., Hall, W., Hides, L., and Leung, J. (2021). Treatment rates for alcohol use disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Addiction, 116(10), 2617-2634. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/add.15357.

- Yimer, T. M., Chan, G. C. K., Connor, J. P., Hides, L., and Leung, J. (2021). Estimating the global treatment rates for depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 295, 1234-1242. DOI: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.09.038.

- Yimer, T. M., Chan, G. C. K., Belete, H., Hides, L., and Leung, J. (2023). Treatment-seeking behavior and barriers to mental health service utilization for depressive symptoms and hazardous drinking: the role of religious and traditional healers in mental healthcare of Northwest Ethiopia. Cambridge Prisms: Global Mental Health, 10, e92. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2023.88.

- Mellor, R., Lancaster, K., and Ritter, A. (2019). Systematic review of untreated remission from alcohol problems: estimation lies in the eye of the beholder. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 102, 60-72. DOI: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2019.04.004.

- Yimer, T. M., Ford, S., Chan, G. C. K., Hides, L., Connor, J. P., and Leung, J. (2022). What is the short-term remission rate for people with untreated depression? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 296, 17-25. DOI: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.09.046.

- Yimer, T. M., Chan, G. C. K., Belete, T., Menberu, M., Davidson, L., Hides, L., and Leung, J. (2022). Mental health service utilization in a low resource setting: a qualitative study on perspectives of health professionals in Northwest Ethiopia. PLoS ONE, 17(11), e0278106. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0278106.

- Baheretibeb, Y., Wondimagegn, D., and Law, S. (2021). Holy water and biomedicine: a descriptive study of active collaboration between religious traditional healers and biomedical psychiatry in Ethiopia. BJPsych Open, 7(3), e92. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2021.56.